The .NET Remoting architecture is based on five core objects:

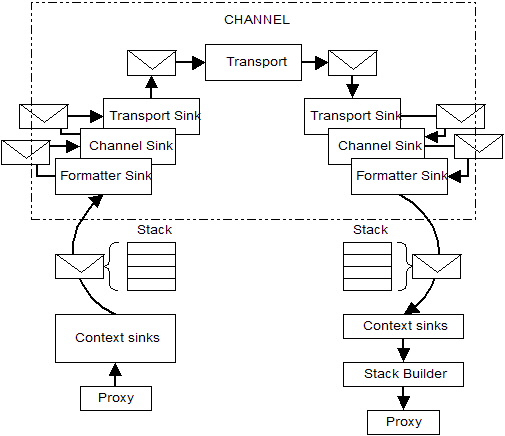

The following figure illustrates the position of these five components within the overall structure of the .NET Remoting Framework:

Instead of having a client deal directly with remote objects, a client only deals with proxies. These are the local representative of remote objects, and hence they provide the same exact interface as the real remote object. Proxies do not execute any methods on their own, but instead they forward each method call to the .NET Remoting Framework as a Message object. This message then passes through a couple of sinks until it finally reaches the server. There, it passes through another set of sinks until the call is placed on the real destination object. The server then creates a return message that will be passed back to the proxy. The proxy handles the message and converts it to the corresponding out/ref parameters and the method's return value, which will be passed back to the client application.

When a client uses new or Activator.GetObject to get a reference to a remote object, the .NET Remoting Framework creates two proxies: The first is an instance of the generic TransparentProxy. This is the object that is returned to the client. Whenever you call a method on the reference to the remote object, you will in fact be calling the method on the TransparentProxy instance. This proxy holds a reference to the second proxy which is an instance of RemotingProxy (RemotingProxy is a descendant of the abstract RealProxy class). Note that during the creation stage, reference to the client-side message sinks are obtained using the sink providers passed during channel creation. These references are stored in the Identity object contained in the RealProxy.

The following code results in the graph below:

HttpChannel chnl = new HttpChannel();

ChannelServices.RegisterChannel( chnl );

SomeRemoteClass obRemote = (SomeRemoteClass)Activtor.GetObject(

typeof(SomeRemoteClass), "http://localhost:1234/SomeRemoteClass.soap"

);

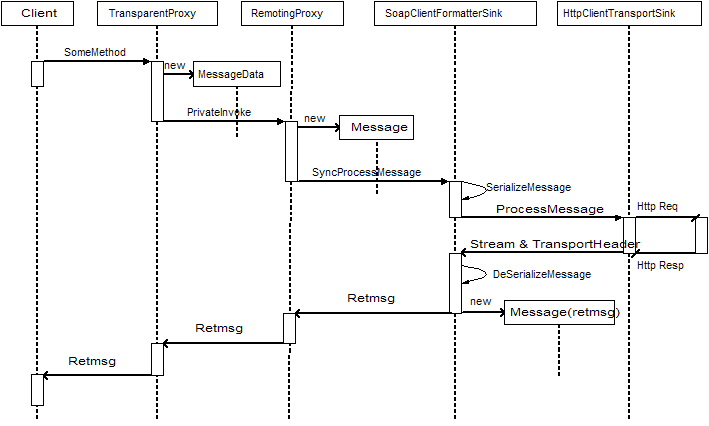

The following discussion refers to the following figure which illustrates client-side synchronous message handling with only two sinks; SoapClientFormatterSink and HttpClientTransportSink::

When a call is placed on a remote object reference, the TransparentProxy creates a MessageData object and passes it to the RealProxy's PrivateInvoke() method. The RealProxy in turn generates a new Message object and calls its InitFields() method, passing the MessageData object as a parameter. The Message object now populates its properties by resolving the pointers inside the MessageData object.

For synchronous calls, the RealProxy places a chain of calls on itself. One of those calls will look up the sink chain (_channelSink object) in the contained Identity object and call SyncProcessMessage() on the first IMessageSink. When the processing, including server-side handling, has completed, the call to this method will return an IMessage object containing the response message. The RealProxy will call its own HandleReturnMessage() method which checks for out/ref parameters and will call PropageOutParameters() on the Message object. Part of this processing is illustrated in the figure above. Note that if the client was using a TCP channel instead of an HTTP, the channel would consist of a BinaryClientFormatterSink and a TcpClientTransportSink.

After handling the response, the RealProxy will return from its PrivateInvoke method and the IMessage is passed back to the TransparentProxy, which will take the return values and out parameters from the Message object and return them to the calling application in the conventional stack-based method return fashion of the CLR.

When working with CAOs, the client needs to distinctly identify remote objects. When passing references to CAOs from one process to another, this identity information has to travel with the call. The identity information is stored in the serializable ObjRef object.

When instantiating a CAO, a serialized ObjRef will be returned by the server to the client. This ObjRef is taken as a base to initialize the Identity object, and a reference to it will also be kept by the Identity object. The ObjRef stores the unique URL to the CAO, as well as the server's base URL which has also been returned by the server.

Note: The behavior described above is very different to SAOs where the URL to the server is specified at the client. With CAOs, only the URL needed for the creation of the CAO is known to the client. The real connection end-point for the CAO will be returned when creating the object. This can also mean that a host behind a firewall might return its private IP address, rendering the CAO unusable. To prevent this behavior, use either the machineName or bindTo attribute in the channel's configuration file.

You can check the ObjRef properties or any other properties of the proxies in VS.NET IDE by setting a breakpoint immediately after you acquire a reference to a remote object (for example, after SomeSAO ob = new SomeSAO() ). Open the Locals debug window and expand the ob entry.

A remote method call is really a message object that goes form the client to the server and possibly back. A message is basically a dictionary object hidden behind the IMessage interface. Even though every message is based on this interface, the .NET Framework defines several types of messages. The main difference between these types of messages is a predefinition of several entries in the internal dictionary. Nonetheless, an object that implements IMessage meets the minimum qualification to be considered a message object.

While traveling through a chain of sinks, the message passes through two important points: a formatter and a transport channel. The formatter is a special sink that encodes the message into a protocol such as SOAP or binary representation. The transport channel transfers a serialized message from one process to another. At the destination, the message's dictionary is restored from the protocol by a server-side formatter. After this, the message passes through a series of sinks until it reaches the dispatcher. The dispatcher converts the message into a stack-based method call that will be executed on the real object.

After execution, a return message is generated for most types (except OneWay calls) and passed back through the various channels and sinks until it reaches the client-side proxy, where it will be converted to the respective value or exception.

Therefore, messages are used to transmit remote method calls, to activate remote objects, and to transfer information. Note that a message object carries a set of named properties, including action identifiers, envoy information, and parameters. Some of the important classes of the System.Runtime.Remoting.Messaging namespace are AsyncResult and ReturnMessage class, among others.

Message sinks are used to transfer messages from a client application to a server-side object. A sink (also known as message sink) receives its message from another object, applies its processing and delegate any additional work to the next sink in the chain.

Message sinks are objects that typically implement one of the basic interfaces for message sinks: IMessageSink, IClientChannelSink, and IServerChannelSink. For example, IMessageSink interface defines two methods for processing a message, SyncProcessMessage and AsynProcessMessage, and a property, NextSink, to acquire a reference for the next sink in the chain. If a sink (client-side or server-side) needs to access the Message object, i.e., before the message is serialized, it must implement IMessageSink. And if a sink needs to access the serialized message stream it must implement IClientChannelSink for client-side sinks, and IServerChannelSink for server-side sinks.

At some point in the chain, the message will reach the formatter (also an IMessageSink) that will serialize the message to a defined format and pass it on to a secondary chain of IClientChannelSink objects. The main difference between IMessageSink and IClientChannelSink is that the former can access and change the original dictionary, independent of any serialization format, whereas the latter has access to the serialized message as a stream.

After processing the message, the IClientChannelSink also passes the message to the next sink in the chain until it reaches a transport channel like HttpClientTransportSink for the default HTTP channel

A Message object needs to be serialized into a stream before it can be transferred to another process. This is the purpose of the formatter. The .NET Remoting Framework provides two default formatters, the SoapFormatter and the BinaryFormatter, which can both be used via HTTP or TCP connections.

After a message completes the pre-processing stage by passing through a chain of IMessageSink objects, it will reach the formatter via the SyncProcessMessage() method. On the client side, the SoapClientFormatterSink passes the IMessage on into its SerializeMessage() method, which sets up the TransportHeaders and asks its NextSink for the request stream onto which the serialized data will be written. The real serialization is started from CoreChannel.SerializeSoapMessage() which creates a SoapFormatter and calls its Serialize() method.

After the last IClientChannelSink (which could be a formatter or a custom sink) has been called, it forwards the message, the stream, and its associated headers to the ProcessMessage() method of the associated transfer channel. The transport sink's responsibility is to convert these headers into a protocol-dependent format - for example, into HTTP headers. The transport channel will then open a connection to the server (or check if it is already opened for TCP channels and HTTP Keep-alive connections) and send the headers and the stream's contents over this connection.

From previous discussion, the message is created by the combination of TransparentProxy and RemotingProxy, which then send it to the first sink of the message chain sink. After this creation, the message will pass through many stages depending on the channel's configuration. This is shown below:

Note that the contents of the pre-processing, formatting, and transfer layers are customizable during channel creation. When creating a default HTTP channel, for example, only a SoapClientFormatterSink (as the formatting layer) and an HttpClientTransportSink (as the transport layer) will be created. By default, neither a pre-processing layer nor any dynamic context sinks are registered.

This sink is automatically registered for all channels. It is the first sink that gets called as shown in the overall .NET Remoting architecture figure, and in turn notifies any dynamic context sinks associated with the current remoting context. As shown in the previous figure, these dynamic sinks receive message via the IDynamicMessgeSink interface. These dynamic sinks in turn do not need to pass information to any other sink as this is handled automatically by the context terminator sink (it calls relevant method on a list of registered dynamic sinks before it passes the message on to the next IMessageSink).

As shown in the figure above, the message reaches the formatter after passing through any optional custom IMessageSink sinks. The formatter's task is to take the message's internal dictionary and serialize it into a wire-format The output of the serialization is an object that implements ITransferHeaders and a stream from which the channel sink will be able to read the data.

The formatter then calls ProcessMessage() on its assigned IClientChannelSink and as a result starts to pass the message to the secondary chain - the channel sink chain.

At the end of the chain of client channel sinks, the message ultimately reaches the transfer channel, which also implements the IClientChannelSink. When the ProcessMessage() method of this IClientChannelSink is called, it open a connection to the server and passes the data using the defined transfer protocol. The server processes the message and returns a ReturnMessage in serialized form. The client-side channel sink will take this data and split it into an ITransferHeader object which contains the headers, and a stream which contains the data. These two objects are then returned as out parameters to the ProcessMessage() method.

After this splitting, the response message travels back through the chain of IClientChannelSinks until it reaches the formatter, where it is de-serialized and an IMessage object is created. This object is then returned through the chain of IMessageSink sinks until it reaches the two proxies. The TransparentProxy decodes the message and generates the method's return value and fills the respective out and/or ref parameters. The original method call placed by the client returns and the client has now access to the method's responses.

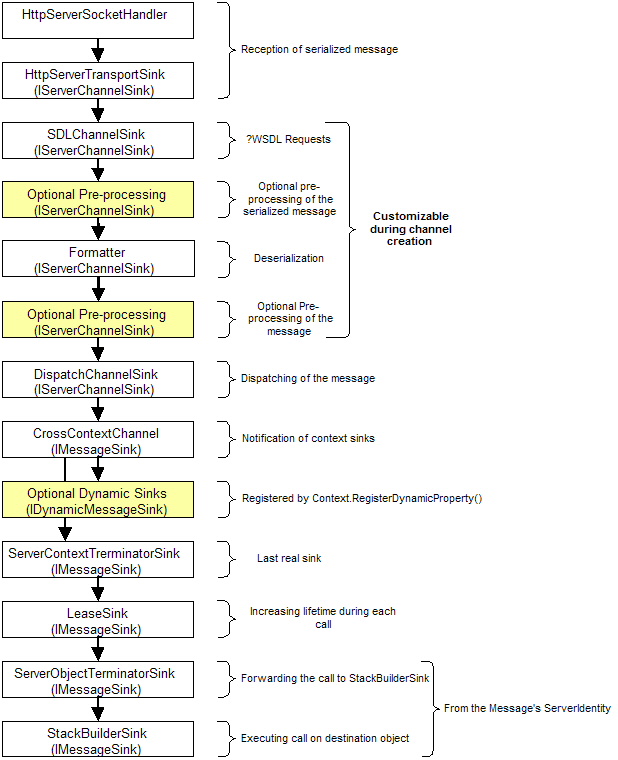

The following discussion refers to the following diagram which illustrates server-side synchronous message handling:

During the creation of the server-side channel, the server-side sink chain is created and a TcpListenter is created in a new thread. This listener object starts to listen on the specified port and notifies the HttpServerSocketHandler when a connection is made from the client.

One of the main differences between client-side and server-side message processing is that on the server side, each sink's ProcessMessage takes a parameter of type ServerChannelSinkStack. Every sink participating in a call pushes itself onto this stack before forwarding the call to the next sink in the chain. The reason for this is that sinks do not know up-front if the call will be handled synchronously or asynchronously. Every sink that has been pushed into the stack will get a chance to handle the asynchronous reply later.

When a connection to the server-side is opened, an instance of HttpServerSocketHandler is created and supplied with a delegate that points to the ServiceRequest() method of the next sink in line, HttpServerTransportSink. This method will be called after the background thread has finished reading the request stream.

HttpServerTransportSink sets up the ServerChannelSinkStack and pushes itself onto this stack before forwarding the call to the next sink, SDLChannelSink.

This sink is a very special kind of sink that illustrates the power of .NET Remoting extensibility. Unlike most other sinks, this sink does not forward any requests to the destination object, but rather, generates the WSDL information needed for the creation of proxies. SDLChannelSink does this whenever it encounters "?WSDL" or "?SDL" strings at the end of an HTTP GET request.

When the HTTP request is a POST request, or when it is a GET request that does not end with the strings "?WSDL" or "?SDL", the message will be passed to the next sink.

The default server-side HTTP channel uses both the SOAP and the binary formatters in a chained fashion. The first formatter that is used is the SoapServerFormatterSink. This sink first checks whether the serialized message contained in the request stream is a SOAP message. If so, the message is deserialized and the resulting IMessage object is passed to the next sink, which is the BinaryServerFormatterSink. If the stream does not contain SOAP-encoded message, it will be copied to a MemoryStream and passed to the BinaryServerFormatterSink. The BinaryServerFormatterSink employs the same logic and passes the message to the next sink.

Both BinaryServerFormatterSink and SoapServerFormatterSink push themselves onto the sink stack only when they can handle the message. If neither BinaryServerFormatterSink nor SoapServerFormatterSink could deserialize the message and the next sink is not another formatter, an exception is thrown.

After passing through an optional layer of IMessageSink objects, the message reaches the dispatcher. The DispatchChannelSink takes the decoded IMessage and forwards it to ChannelServices.DispatchMessage(), which checks for disconnected or timed-out objects and dynamically instantiates SAOs if they do not exist on the server. After creation of the destination object, DispatchChannelSink passes this call to CrossContextChannel.

The CrossContextChannel notifies dynamic context sinks and passes the IMessage on to the next sink, ServerContextTerminatorSink. A dynamic sink implements IDynamicMessageSink. These sinks do not have to call any additional sinks in the chain, as this will be taken care of by the Framework.

This sink is the last hardwired sink and therefore, has no direct references to other sinks in the chain. To execute the method call specified in the message, ServerContextTerminatorSink gets the ServerIdentity object of the IMessage and requests the object's message sink chain using ServerIdentity.GetServerObjectChain().

The LeaseSink will have a reference to the lease associated with the destination MarshalByRefObject. The LeaseSink simply calls RenewOnCall() method of this lease and passes the call on to the next sink. The RenewOnCall() method gets the RenewOnCallTime configuration setting and sets the object's lifetime to live to this value.

The ServerObjectTerminatorSink will forward the call to the StackBuilderSink. StackBuilderSink uses several functions to create a stack frame (to make a transition between message-based execution and stack-based execution) and calls the destination method. It then generates a return message with the result and values form any out/ref parameters. This ReturnMessage object is returned from the call to SyncProcessMessage().

The previous sections covered only synchronous processing between client and server. This section discusses asynchronous message handling using methods in the IMessageSink and IClientChannelSink interfaces.

When handling messages in a synchronous manner in an IMessageSink chain, the response message will be the return value of the method call. The following shows a code snippet for a simple sink:

class MySink : IMessageSink

{

IMessageSink snkNext;

IMessage SyncProcessMessage( IMessage msg )

{

// Do something with the message object

before sending it to the next sink in the chain

...

// Send the message to the next sink in the chain

IMessage msgReturn = snkNext.SyncProcessMessage( msg );

// Do something with the message object

before returning it to the previous sink in the chain

...

// Then return the return message back to the previous sink

return msgReturn;

}

}

When implementing asynchronous processing using a delegate's BeginInvoke() method, the call to snkNext.AsyncProcessMessage() returns immediately. The response message is sent to a secondary chain, which is passed in the replySink parameter of snkNext.AsyncProcessMessage(). This is how you do asynchronous processing when you do not want to be notified of the method's return:

public class MySink : IMessageSink

{

IMessageSink snkNext;

IMessageCtrl AsyncProcessMessage( IMessage msg, IMessageSink

replySink )

{

// Do something with the message object

before sending it to the next sink in the chain

...

// Send the message to the next sink in the chain.

This call will return immediately

IMessage msgReturn =

snkNext.AsyncProcessMessage( msg, replySink );

// Then return the return message back to the previous sink

return msgReturn;

}

}

If you do want to handle the reply message in a sink of your own, you have to instantiate a new IMessageSink object and chain it to the existing list of reply sinks:

/* This sink is used to handle the

asynchronous response */

public class MyReplySink : IMessageSink

{

IMessageSink snkNext;

// Constructor. Connect this sink to the chain

public MyReplySink( IMessageSink next )

{

snkNext = next;

}

IMessageCtrl SyncProcessMessage( IMessage msg )

{

// msg is the reply message from the asynchronous calls. Do something with the message if

needed

...

// Then pass it on to the next sink in the reply chain

IMessage msgReturn = snkNext.SyncProcessMessage( msg );

return msgReturn;

}

}

public class MySink : IMessageSink

{

IMessageSink snkNext;

IMessageCtrl AsyncProcessMessage( IMessage msg, IMessageSink replySink )

{

// Do something with the message object before sending it to the next sink in the chain

...

// Create a new reply sink which is chained to the existing replySink

IMessageSink obReplySink = new MyReplySink( replySink );

// Send the message to the next sink in the chain. This call will return immediately

IMessage msgReturn = snkNext.AsyncProcessMessage( msg, obReplySink );

// Then return the return message back to the previous sink

return msgReturn;

}

}

Note that the reply message is processed synchronously. Only the generation of the message happens asynchronously at the server.

IClientChannelSink interface has distinct methods for handling asynchronous request and reply, AsyncProcessRequest() and AsyncProcessResponse(). When AsyncProcessRequest() is called while an IMessage travels through a sink chain, it receives an IClientChannelSinkStack which acts as a stack of sinks that want to be notified when the asynchronous processing returns. If your sink wants to be included in the notifications, it must push itself onto the stack before calling the next sink's AsyncProcessRequest():

public class MySink : IClientChannelSink

{

IClientChannelSink snkNext;

public void AsyncProcessRequest( IClientChannelSinkStack

sinkStack,

IMessage msg,

ITransportHeaders headers,

Stream stream )

{

// Do something with the message object before sending it to the next sink in the chain

...

// Push this sink onto the stack in order to receive notification of asynchronous result

sinkStack.Push( this, null );

// Send the message to the next sink in the chain. This call will return immediately

IClientChannelSink msgReturn =

snkNext.AsyncProcessRequest( sinkStack, msg, headers, stream );

// Then return the return message back to the previous sink

return msgReturn;

}

public void AsyncProcessResponse( IClientChannelSinkStack

sinkStack,

object State,

ITransportHeaders headers,

Stream stream )

{

// Work with

stream and/or headers

...

// Call the

next sink via the sink stack

sinkStack.AsyncProcessResponse(

headers, stream );

}

}

Note that regardless of whether the request is synchronous or asynchronous, the IMessageSink chain is always handled before any calls to IClientChannelSink.

On the server-side there are two kinds of interfaces: IServerChannelSink and IMessageSink. The asynchronous processing for objects implementing IMessageSink is handled in the same way as on the client: The sink creates another reply sink and passes it to the AsyncProcessMessage() method of the next sink.

IServerChannelSink objects handle asynchronous messages a bit differently. IServerChannelSink has two methods: ProcessMessage() and AsyncProcessResponse(). When a serialized message is received by an object implementing this interface, it is not yet determined whether it will be handled synchronously or asynchronously. This can only be defined after the message reaches the formatter. Until that happens, the sink assumes that the response will be handled asynchronously and therefore, pushes itself (and a possible state object) on the stack before calling the next sink.

The call to the next sink returns a ServerProcessing value that can have a value of Completed, Async, or OneWay. The sink has to check if this value is Completed and only in such a case that it can do any post-processing work in ProcessMessage(). If this returned value is OneWay, the sink will not receive any further information when the processing has finished.

When the next sink's return value is ServerProcessing.Async, the current sink will be notified via the sink stack when the processing has been completed. The sink stack will call AsyncProcessResponse() in this case. After the sink has completed the processing of the response, it has to call sinkStack.AsyncProcessResponse() to forward the call to further sinks.

public ServerProcessing ProcessMessage( IServerChannelSinkStack sinkStack, ...

/* others */ )

{

// Handle the request here as required

...

// Because we do not know if this is asycn or sync yet, we need to push this sink onto the stack

sinkStack.push( this, null );

// Send over to the next sink

ServerProcessing srvrProcessing = sinkNext.ProcessMessage( sinkStack, ...

/* others */ );

if (srvrProcessing = ServerProcessing.Complete)

{

// Handle response here as required

}

// Return status information

return srveProcessing;

}

public void AsyncProcessResponse( IServerResponseChannelSinkStack sinkStack, ...

/* others */ )

{

// Handle the response here

...

// Forward the message to the stack for further processing

sinkStack.AsyncProcessResponse( msg, headers, stream );

}