Sinks are normally not created directly in either your code or with the definition in configuration files. Instead, a chain of sinks providers is set up, which will in turn return the sink chains on demand. Channel providers or channel sink providers are objects that implement IClientChannelSinkProvider, IClientFormatterSinkProvider, or IServerChannelSinkProvider and are responsible for creating the channel sinks through which remoting messages flow. A provider can be either client-side or server-side.

You can define a chain of sinks in a .NET configuration file as shown below:

<!-- Client-side configuration

file. For server-side replace clientProviders element with serverProviders

-->

<configuration>

<system.runtime.remoting>

<application>

<channels>

<channel ref="http">

<clientProviders>

<provider type="MySinks.SomeMsgSinkProvider, Client" />

<formatter ref="soap" />

<provider type="MySinks.SomeClientChannelSinkProvider, Client" />

</clientProviders>

</channel>

</channels>

</application>

</system.runtime.remoting>

</configuration>

Note that the chain is setup using a chain of sink providers and not a chain of sinks (if the formatter element was expanded to include the real type as defined in the machine.config file, it would also have a type that refers to a provider, in specific, SoapClientFormatterSinkProvider.

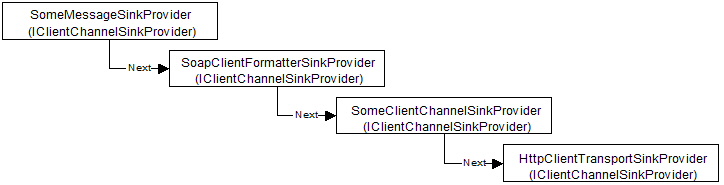

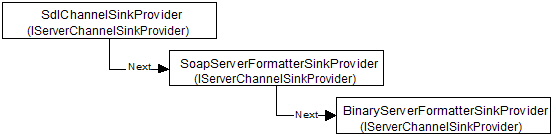

After an application loads the configuration file shown previously, a provider chain will be set up as shown below. Note that the first three providers are the ones specified in the configuration file:

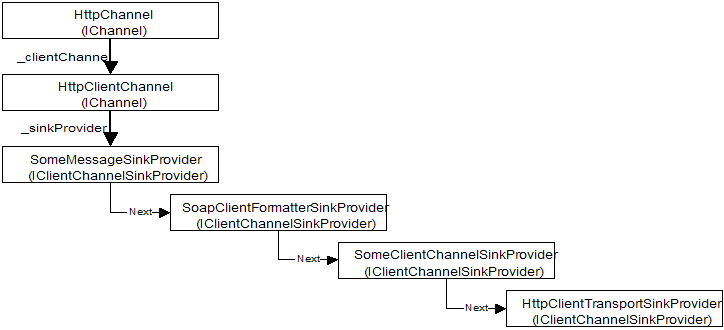

On the client side, these sink providers are associated with the client-side channel, which can be accessed using the following code:

IChannel chnl = ChannelServices.GetChannel( "http" ); // "http" refers to the channel's real name as setup in machine.config

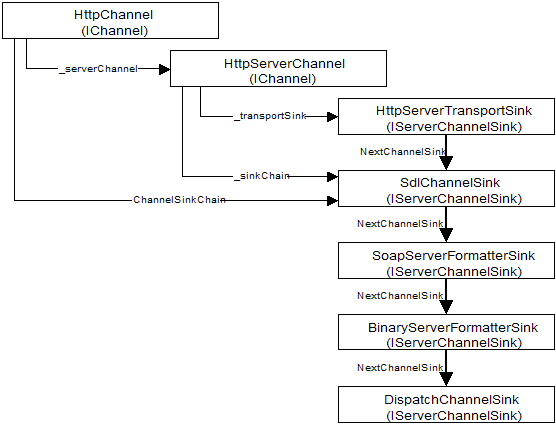

Creation of the chnl channel object results in the creation of the following sink chain:

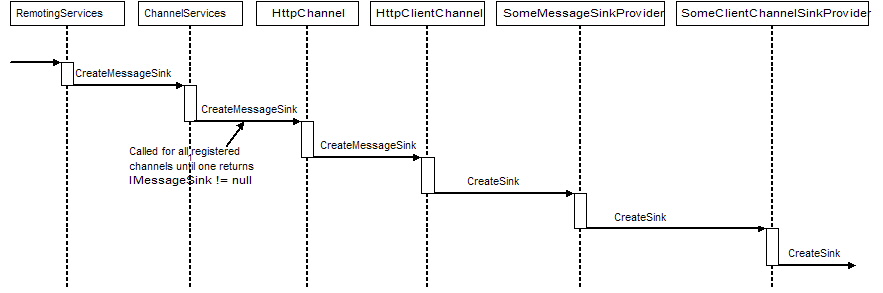

Many things happen behind the scene when a reference to a remote SOA is created. At some point during the use of the new keyword or Activator.GetObject() method, RemotingServices.Connect() method will be called. What happens next is shown below:

ChannelServices calls CreateMessageSink() on each registered channel until one of them accepts the URL passed as a parameter. The HTTP channel for example will work on any URL that starts with http or https, whereas the TCP channel will only accept those with a tcp: protocol designator. When a channel recognizes the URL, it will call CreateMessageSink() on its client-side channel.

HttpClientChannel then invokes CreateSink() on the first sink provider given in the configuration file. The following code corresponds to what the different sink providers will do:

public class SomeClientChannelSinkProvider : IClientChannelSinkProvider

{

private IClientChannelSinkProvider next = null;

public IClientChannelSink CreateSink(IChannelSender channel, string url, object remoteChannelData)

{

IClientChannelSink nextSink = null;

// Check for additional sink proivders

if (next != null)

{

nextSink = next.CreateSink(channel, url, remoteChannelData);

}

// return the first entry of a sink chain

return new SomeClientChannelSink( nextSink );

}

}

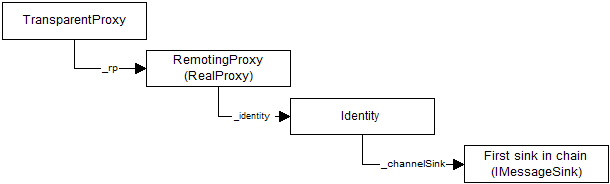

Each sink provider first calls CreateSink() on the next entry in the provider chain and then returns its own sink on top of the sink chain returned from this call. The complete sink chain that is returned from the call to ChannelServices.CreateMessageSink() is then connected to a new TransparentProxy / RealProxy pair's identity object as shown below:

Creating server-side sinks is a little bit different from creating client-side sinks. As shown previously, on the client side the necessary sinks are created when a reference to a remote object is registered. When a server-side channel is created from a definition in a configuration file, the following constructor is used:

public HttpServerChannel(IDictionary properties, IServerChannelSinkProvider snkProvider);

Note that the IDictionary contains the contents of the <channel> section. For example, if the configuration file contained <channel ref="http" port="12345"/>, then the properties dictionary will contain one key/value pair of ("port", 12345).

During the channel setup which is started from the HTTP channel's constructor shown above, one of two things will now happen:

Both client-side and server-side sink chain can call dynamic sinks. On the server-side this is done by the CrossContextChannel and on the client side by the ClientContextTerminatorSink. Dynamic sinks are associated with a specific context and therefore will be called for calls passing a context boundary. They cannot be assigned to a specific channel and will even be called for local cross-context or corss-AppDomain calls. The sinks are created by dynamic context properties which are classes implementing IDynamicProperty and IContributeDynamicSink. The IContributeDynamicSink can be compared to a sink proivder for dynamic sinks. Note that the dynamic sink itself implements the IDynamicMessageSink interface.

The following dynamic sink will write a trace statement whenever a message passes through a remoting boundary:

public class MyDynamicSinkProvider : IDynamicProperty,

IContributeDynamicSink

{

// Interface implementation: IDynamicProperty

public string Name

{

get { return "MyDynamicSinkProvider"; }

}

// Interface implementation: IContributeDynamicSink

public IDynamicMessageSink GetDynamicSink()

{

return new MyDynamicSink();

}

}

public class MyDynamicSink : IDynamicMessageSink

{

// Interface implementation : IDynamicMessageSink

public void ProcessMessageStart(IMessage msgRequest, bool bClientSide, bool bAsyn)

{

Console.WriteLine( "MyDynamicSink.ProcessMessageStart" );

}

public void ProcessMessageFinish(IMessage msgReply, bool bClientSide, bool bAsyn)

{

Console.WriteLine( "MyDynamicSink.ProcessMessageFinish" );

}

}

To register a dynamic property with the current context:

Context ctxt = Context.DefaultContext;

IDynamicProperty prp = new MyDynamicSinkProvider();

Context.RegisterDynamicProperty( prp, null, ctxt );