As seen from the last chapter, there are two different types of remote interactions between components:

Marshaling objects by-value means to serialize their state (instance variables) including all objects referenced by instance variables, to some persistent form from which they can be deserialized in a different context. It is important to understand that by-value objects are not remote objects. All methods on those objects will be executed locally in the context of the caller. This means that unlike MarshalByRefObjects, the compiled class must be available to the client as well as the server.

The ability to serialize/deserialize an object is provided by the .,NET Framework when you set the [Serializable] attribute or implement the ISerializable interface. For example, in the example of the previous section, the Customer object is serialized into an XML document before being sent to the remote client. This XML document will be ready at the client and an exact copy of the object created:

<a1:Customer id="1">

<FirstName id="2">Yazan</FirstName>

<LastName id="3">Diranieh</LastName>

<DOB id="4">1 1 1990</DOB>

</a1:Customer>

When a by-value object holds references to other objects, these have to be either serializable or MarshalByRefObjects. Otherwise, an exception indicating the the object is not remotable will be thrown.

A MarshalByRefObject is a remote object that runs on the server and accepts method calls from a client. The object's data is saved in the server's memory and its methods are executed in the server's AppDomain. Instead of passing around a variable that points to this kind of object, .NET passes around a networked pointer called ObjRef. Contrary to a common pointer, this pointer does not contain a memory address, but rather a server IP/Object ID pair that uniquely locates an object on any network.

In general, MarshalByRefObjects can be categorized into two groups:

Server-activated objects are somewhat comparable to classic stateless Web Services. Note the following key facts about SAOs:

SingleCall objects are registered on the server using the following statement:

RemotingConfiguration.RegisterWellKnownServiceType( typeof("<You Class>"), "<URL>", WellKnownObjectMode.SingleCall );

Objects of this kind obviously can hold no state information as all internal variables will be discarded at the end of the method call. SingleCall objects can be deployed in a very scalable manner. These objects can be loaded on different servers with a load-balancing mechanism which would not be possible when using stateful objects.

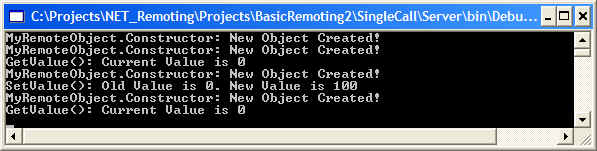

The following is output from project Single Call which illustrates how to write a SingleCall object. The top window is that of the client and the bottom one is that of the server:

The constructor traces in the bottom window indicate that an object is created for each call, GetValue(), followed by SetValue() followed by GetValue(). Note that the first constructor trace indicating that a new object was created refers to the fact than an object is created the first call as well.

Only one instance of a Singleton object can exist at any given time. When receiving a client's request, the server checks its internal tables to see if an instance of the requested object is already running. If not, the object will be created and stored in the server's internal tables. After this check, the method will be executed. The server guarantees that exactly one or no instance will be running at any given time. Use Singletons when you want to share data or resources between clients.

Note that Singleton's have an associated lifetime as well. Be sure to override the standard lease time if you do not want your objects to be destroyed after some few minutes. More on this later in this section. Singleton objects are registered on the server using the following statement:

RemotingConfiguration.RegisterWellKnownServiceType( typeof("<You Class>"), "<URL>", WellKnownObjectMode.Singleton );

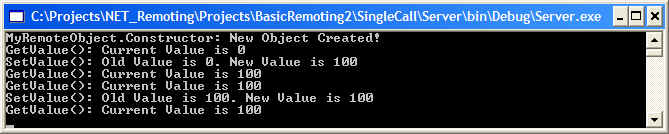

The following is output from project Single Call except that the WellKnownObjectMode value was set to Singleton as above. The first two screens refer to clients and the third screen refers to the server. A client (window 1) was started, and then another client (window 2) was started. Note that client 2 (window 2) get an original server-side value of 100, which is the value set by the first client. Looking at the server's output in the third window, note that the server-side object was created once and only once:

When using either SingleCall or Singleton objects, the necessary instances will be created dynamically during a client's request. When you want to publish a certain object that has been precreated on the server, then neither option (SingleCall or Singleton) provides you with a solution.

In this case, you can use RemotingServices.Marshal to publish a given instance that behaves like a Singleton afterwards. The only difference is that the object must already be created before publishing it. RemotingServices.Marshal converts the given MarshalByRefObject into an instance of ObjRef class, which can then be serialized for transmission between application domains and over the network. The code in the server will look something like:

/* Server-side startup code

using RemotingServices.Marshal to publish a precreated object */

class ServerStartup

{

[STAThread]

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// All of the following three calls are from System.Runtime.Remoting namespace

Channels.Http.HttpChannel chnl = new

System.Runtime.Remoting.Channels.Http.HttpChannel( 1234 );

Channels.ChannelServices.RegisterChannel( chnl );

// Publish the

object

SomeRemoteObject ob = new

SomeRemoteObject( 1000 ); //

1000 is the initial value (not port number!)

RemotingServices.Marshal( ob, "SomeRemoteObject.soap"

);

// Keep the server running until a key-press

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

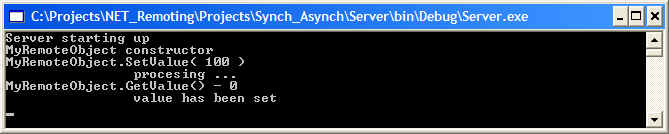

Recall that MarshalByRefObjects can be categorized into two groups: Server-Activated Objects (SAO), and Client-Activated Objects (CAO). A CAO behaves mostly the same way as does a normal .NET object (or a COM object). Client-activated objects are objects whose lifetime is controlled by the calling application domain, exactly like a normal local .NET object (contrast this to SAOs where the object's lifetime was controlled by the server). When a creation request is encountered on the client, using Activator.CreateInstance or new, an activation request is sent to the server, where a remote object is created. On the client, a proxy that holds the ObjRef received from the server is created, exactly the same as in the SAO scenario.

Each time a client creates an instance of a CAO , that instance will service that particular reference in that particular client until the lease expires or the memory is recycled. If the calling application domain creates two new instances of the same type, each of the client references will invoke only the particular instance in the server application domain from which the instance was obtained.

A client-activated object's lifetime is managed by the same lifetime service used the by SAOs. CAO's are stateful objects: An instance variable that has been set by the client can be retrieved again and will contain the correct value. These objects store information from one method call to another. CAOs are explicitly created by the client, so they can have normal constructors just like any normal .NET object.

The .NET Remoting Framework can be configured to allow client-activated objects to be created like normal .NET objects using the new operator. Unfortunately, with this method you cannot use shared interfaces or base classes. This means you either have to ship the code to clients, or use SoapSuds to extract metadata. Unfortunately, it is not currently possible to call non-default constructors when using SoapSuds generation mechanism. When the application needs this functionality, use the class factory-based approach discussed after this section or rely on SoapSuds -gc parameter to manually enhance the generated proxy.

The following example will use the same server class seen previously: it will provide SetValue and GetValue methods. The metadata needed by the client to create a CAO will be extracted with SoapSuds.exe. The reliance on SoapSuds allows you to develop the server without any need for an up-front design of a shared assembly, therefore, the server will only include the CAO implementation. In other words, there will be no 'General.dll' shared assembly that must be reference by both client and server projects.

Note that in the server application when adding a CAO type to the list of activated objects, you cannot provide a single URL for each object as is the case in SAO objects. Instead you have to set RemotingConfiguration.ApplicationName property to a value that identified the server. The URL to the remote CAO object will be http://<hostname>:<port>/<ApplicationName>. What happens behind the scenes is that a general activation SAO is automatically created at http://<hostname>:<port>/<ApplicationName>/RemoteActivationService.rem . This SAO will take the client's requests to create a new instance and pass it over to the .NET Remoting Framework.

The overall basic steps to create this sample were:

soapsuds -ia:server.exe -nowp -oa:CAOMetadata.dll

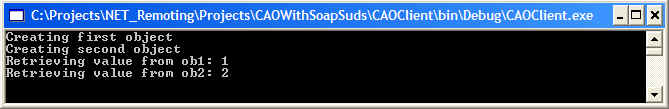

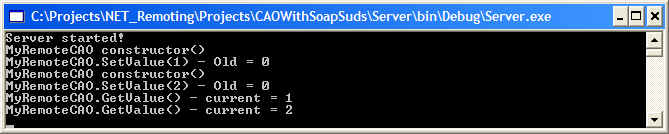

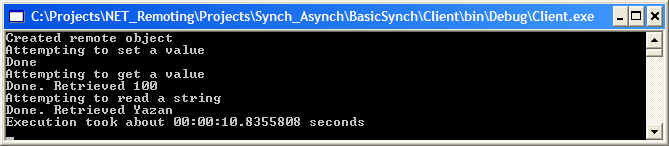

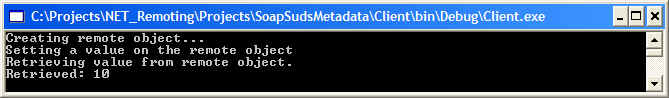

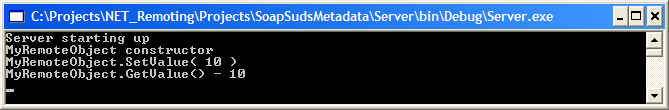

The following illustrates output from the CAOWithSoapSuds project. Note that client has two separate instances of the CAO object with each instance having its own state.

As mentioned previously, SoapSuds.exe cannot extract metadata for non-default constructors. When a client's design requires that CAO objects have non-default constructors, the recommended approach is to use a factory design pattern (see Factory pattern under Design Patterns section in the left-hand Contents frame for more information). The basic approach is to create an SAO that provides methods that return the required new instances of some CAO. In other words, due to constraints on the real object, you will not be able to construct it directly. Instead, you will have to call a method on the SAO (the factory) which creates a new instance and passes it back to the client.

You can ship the server-side assembly and reference it in the client but this approach goes against all distributed application design functionality. Think of what you have to do if you found a bug in the server implementation - Redistribute to n users where n can be 100 or 1000 or 10,000 or more!

The following shows a fairly simple implementation of this pattern:

// The class to be created by the

factory

class MyClass { ... }

// Handles creating instances of

MyClass

class MyFactory

{

public MyClass GetNewInstance() { return new MyClass(); }

}

class MyClient

{

static int Main()

{

// Creating

MyClass directly using new

MyClass ob1 = new MyClass();

// Creating

MyClass using a class factory

MyFactory f = new MyFactory();

MyClass ob2 = f.GetNewInstance();

}

}

When bringing this pattern to remoting, you have to create factory running as an SAO, ideally singleton that has a method that returns a new instance of the CAO. This gives you a huge advantage by not having to distribute the implementation to the client system or manually tweak the output from SoapSuds.exe with -gc option. The following are the main design points for implementing an SAO factory that returns a CAO:

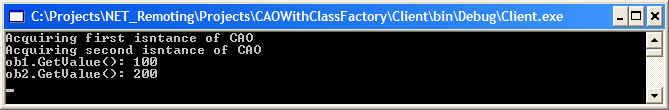

The following is output from CAO With Class Factory project that illustrates a client requesting two CAO objects from an SAO factory:

One point that often leads to confusion is the way an object's lifetime is managed in the .NET Remoting Framework. Common .NET objects are managed using a garbage collection algorithm that checks if any object is still using a given instance. If not, the instance will be garbage collected and disposed.

When the above schema or the COM way of maintaining reference counts is applied to remote objects, the remote objects ping the client-side proxies at predetermined intervals to determine if they are still alive or the application is still running. The reason for this is that the client may close unexpectedly due to a crash or a network outage. In this case, the client will not have had a chance to decrement the reference count on the remote objects, hence these objects will stay in server's memory forever, consuming valuable resources. Unfortunately, the above scheme cannot be applied when remote clients are behind HTTP proxies accessing remote objects using SOAP, because the server will not be able to contact the client in any way.

This constraint leads to a new kind of lifetime service: the lease-based object lifetime. The main mechanism is as follows:

To change the default times you can override InitializeLifetimeService in MarshalByRefObject class. Also note that the LeaseManager polls all leases every 10 seconds. You can change this default value using LeaseManagerPollTime method of LifetimeServices class. The following code snippets show you what need to be done:

class ServerWithClassFactory

{

[STAThread]

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Console.WriteLine( "Server starting up" );

// Setup the lease manager time

LifetimeServices.LeaseManagerPollTime = TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds( 1000 );

// As usual, register a channel

HttpChannel chnl = new HttpChannel( 1234 );

ChannelServices.RegisterChannel( chnl );

Console.ReadLine();

...

}

}

class MyRemoteObject : MarshalByRefObject, SharedAssembly.IRemoteObject

{

...

// Overrides (use class view to view what functions are available for base classes/interfaces)

public override object InitializeLifetimeService()

{

Console.WriteLine("MyRemoteObject.InitializeLifetimeService() called");

ILease lease = (ILease)base.InitializeLifetimeService();

if (lease.CurrentState ==

LeaseState.Initial)

{

lease.InitialLeaseTime = TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds( 1000 );

lease.SponsorshipTimeout = TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds( 1000 );

lease.RenewOnCallTime = TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds( 1000 );

}

return lease;

}

}

Irrespective of the type of the remote object (Singleton, SingleCall or published objects), the .NET Framework provides three ways to call them: synchronous, asynchronous, and one-way asynchronous.

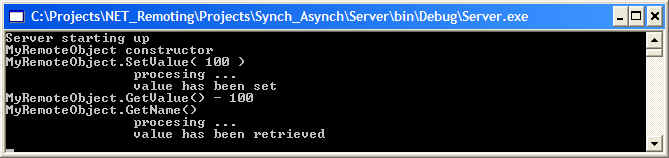

The following section contains mostly examples. The server and the shared assembly will be the same in each example. The server serves a Singleton object with a get/set methods. In both get and set methods, we introduce a five-second sleep in order to illustrate the effects of long-lasting executions in different execution contexts.

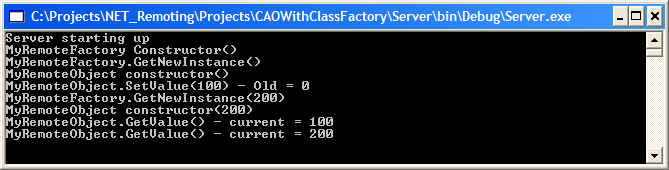

When running this application, you will have to wait until the server completes processing of each call. At the end of the client screen shot, note that it took around 10.8 seconds to complete two method calls. Output taken from project Synchronous Remote Calls:

In the synchronous calls example above, you had to wait for each call to complete and this incurs performance penalty. Asynchronous calls in .NET are provided through through asynchronous delegates, that allow method to be called in an asynchronous fashion.

How do you declare a delegate? Recall that a delegate is really an object-oriented function pointer. You pass the delegate a function to be called when the delegate is invoked. In the .NET Framework, a delegate is a class derived from System.MulticastDelegagte, but C# provides an easier way to work with delegates instead of having to create a new class. The declaration of a delegate in C# look to declaring a function:

delegate <ReturnType> <Name> ( [parameters,] )

And because a delegate will a method at some point in the future, you will have to provide the delegate with the exact signature of the method to be called. Also remember that a delegate is just really a class, so you cannot define it within a method's body - only within a namespace or another class. The following example shows how to declare a delegate:

/* We want the delegate to call this

function */

public String Myfunction(int nVal);

/* Here is the delegate declaration that calls the above

function. Note that the delegate's parameter and return type must match those

of the method to be called */

delegate String MyDelegate( int nVal );

How do you invoke a delegate? Well, it's a class, so the first step is to instantiate it, passing the method to be called as the constructor's parameter.

MyDelegate del = new MyDelegate( MyFunction ); // Note that MyFunction is not given any paraenthesis, i.e., ()

The second step is the invocation. The invocation step itself is a two step process. First, you have to call BeginInvoke() passing the parameters of the method to call, followed by two other objects, which we will always pass them a null value. BeginInvoke() returns an IAsyncResult object that will be used later to retrieve the result of the call:

int nParam = 100; //

The one and only parameter of the method to be called by the delegate

IAsyncResult ar = del.BeginInvoke( nParam, null, null );

How do you retrieve the value of asynchronous delegate call? You call EndInvoke() on the delegate passing the IAsyncResult object obtained from calling BeginInvoke(). The EndInvoke() blocks until the server has finished processing the underlying call:

String strResult = del.EndInvoke( ar );

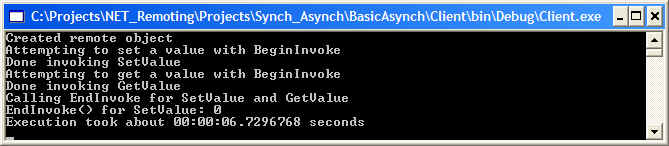

The following example modifies the call used in Example With Synchronous Calls to call the server method asynchronously. In this instance, the same server and shared assembly are used as in the previous example. Note that in the client code, all new code is flagged with: // New: asynchronous.

The previous two screen shots show the output from Asynchronous Remote Calls. Note the reduced invocation time compared to synchronous execution.

Asynchronous one-way calls are different from asynchronous calls in the respect that the .NET Framework does not guarantee their execution. In addition, methods called in this kind of call cannot have returns values or out parameters. You also use delegates to invoke one-way asynchronous calls but EndInvoke() returns immediately without checking if the server has finished executing. No exception are thrown even if the server is down or if the call is malformed. You can use this kind of call in non-critical situations such as error logging or tracing, where the non-existence of the server should not slow down the application.

You define one-way asynchronous calls with the [OneWay] attribute. This should happen in the defining metadata (in Shared.dll or General.dll in these examples) and does not need any change in the client or server. In other words, the [OneWay] attribute must be specified in the interface definition for each method that will be called this way. This attribute is applied at the method level and not the interface level.

The previous Asynchronous Remote Calls example can be easily adapted to use one-way asynchronous calls. Update General.dll assembly by annotating one method with the [OneWay] attribute. On the server side, no change is needed. On the client, no change is needed, but you can extend it by adding a try-catch exception block to catch the eventual exception during execution.

Note: Always remember that a client using [OneWay] calls on a remote object will ignore the server's output and will not even check if the server is running.

This section deals with the issues to consider when using multiple servers in an application in which objects from one server will be passed as method parameters to another server.

MarshalByRefObjects, as the name implies, are object that are marshaled across execution boundaries by reference, instead of passing an entire copy of the object across these execution boundaries. When using MarshalByRefObjects only a 'network pointer' known as ObjRef will travel across execution boundaries. As mentioned previously, an ObjRef is not a regular C++ pointer that that points to a memory address, but rather it is like a 'network pointer' in the sense it contains an IP address to identify the remote server and an object ID to identify which object to access on that remote server. On the client side, an ObjRef is encapsulated by proxy objects ( more on these in Inside the .NET Framework section).

The following figure illustrates a client that has created two CAOs on a remote server. For each CAO, the client will hold a TransparentProxy object, which in turn hold an ObjRef that points to the actual CAO:

Here is what happens when a variable is referencing a MarhsalByRefObject is passed to another remote function: The ObjRef, which is serializable, is taken from the proxy object and serialized and is passed to the remote function (a second server in this example). On the remote machine, new proxy objects are generated from the de-serialized ObjRef. Any calls from the second remote machine to the remote object referred to by ObjRef are placed directly on the first server without any intermediate steps from the client. Note that as the second server will directly contact the first server, there must be some means of communication between them over a network. For example, if there is a firewall between the two server, you will have to configure the firewall to allow communication across these two servers.

Note: This project changes the approach from using abstract interfaces in a shared assembly to using abstract base classes. The reason is that when passing a MarshalByRefObject from server A to server B, the ObjRef is serialized and deserialized. During deserialization on server B, the .NET Remoting Framework will generate a new proxy object and will try to downcast to the correct type (from MarshalByRefObject to MyRemoteObject in this example). This is possible because ObjRef contains information about its type and class hierarchy. Unfortunately, the the .NET Remoting Framework will not serialize the interface hierarchy in the ObjRef object. so these interface casts would not succeed.

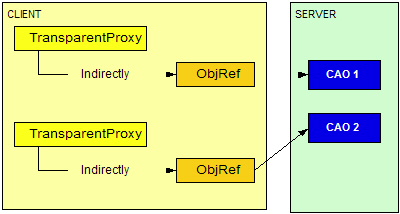

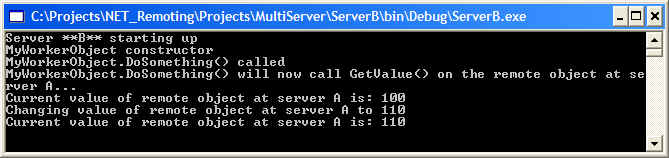

The following is output from project Multi Server. In this scenario, the client creates a remote object on server A and sets/gets values as per normal remote object calls. The client then sends its reference to the remote object on server A to a remote object on server B. The remote object on server B then makes a call on the object it has received. This means that the remote object on server B will call the remote object on server A:

.NET Remoting applications often need to share common information about remotable types between client and server. Contrary to other remote schemas like CORBA and COM, .NET Remoting gives you four ways for writing these shared interfaces and types:

The first and least-favored way to share information about remotable types is to implement your server-side objects in a shared assembly and deploy this to the client as well. The main advantage is that you do not have to do any extra work. This option violates the core principles of distributed application development. Just think of what would happen if you deployed this shared assembly to 3000 remote clients all over the world just to find a bug in this shared assembly a few weeks later.

Nonetheless, there are scenarios where this approach of implementing the server in a shared assembly can be a valid option. For example, you may have an application that can be used in connected and disconnected scenarios and you want to access the same logic in both cases. This approach will allow you to easily switch between using the local implementation and the remote one.

With this approach, you create a shared assembly that is copied to both client and server. This shared assembly will contain the interfaces that will be implemented by the server. The main disadvantage to using this approach of sharing the metadata is that you will not be able to pass those objects as parameters to functions running in a different context (either on the same or another server, or another client). This is because the resulting MarshalByRefObject cannot be down-cast to these interfaces.

Instead of sharing interfaces between client and server, you can also create abstract base classes in shared assemblies. The server-side object will inherit from these classes and provide its own implementation. The main advantage is that abstract base classes, contrary to shared interfaces, can be passed around as parameters to other functions located in different AppDomains. The main advantage of this object is that you cannot use these objects wihtout Activator.GetObject() method or a factory.

SoapSuds functionality is to extract metadata from a running server or an implementation assembly and generate a new assembly that only contains this metadata. You can then reference this assembly in the client application without manually generating any intermediate assemblies.

SoapSuds is a command line utility, so the easiest way to start it is to select Visual Studio.NET Command Prompt from Start -> Programs -> Visual Studio.NET -> Visual Studio.NET Tools. This command prompt will have the correct paths set so you can execute .NET Framework SDK tools fro any directory. Note that starting SoapSuds without any parameters will give you detailed usage information.

To generate a metadata DLL from a running server, you have to call SoapSuds with the -url parameter (-nowp is short for 'no wrapped proxy', which is explained below):

SoapSuds -url:<URL> -oa:<OUTFILE>.dll -nowp

and to generate DLL metadata from an implementation assembly, you have to use the -ia parameter:

SoapSuds -ia:<assembly> -oa:<OUTFILE>.dll -nowp

When you run SoapSuds in its default configuration without the use of the -nowp parameter, it will create what is called a wrapped proxy. A wrapped proxy, also known as a simple proxy, automatically loads all channels, exposes all the methods of the remote object, and provides access to the channel properties. Specifying -nowp will generate a transparent proxy that exposes all the methods of the remote object.

A wrapped proxy is useful when you want to access a third party Web Service whose application URL is known. Using wrapped proxy is also recommended only you want to quickly test a SOAP remoting service. A wrapped proxy is a proxy that can only be used on HTTP channels and will directly store the path to your server, i.e., it will hard-code the server's URL. Normally, this is not what you want since your remote object server may be located on different machines, say during development and deployment and you may want to dynamically configure it to use HTTP or TCP.

To develop a client/server application where the client uses a wrapped proxy you need to do the following:

The Metadata With SoapSuds project shows how to implement a server without previously specifying any shared interfaces or base classes. The output is shown below

Using SoapSuds with the -gc parameter instead of the -oa:<AssemblyName> parameter will generate C# code in the current directory. You can then manually compile this code to produce the assembly that would have been produced with the -oa parameter, or you could include this code in your client project instead.

SoapSuds allows the generation of non-wrapped proxy metadata as well. In this case, it will only generate empty class definitions, which can then be used by the underlying .NET Remoting TransparentProxy to generate true method calls, no matter which channel you are using.

This approach gives you the huge advantage of being able to use configuration files for your channels, objects, and the corresponding URLs so that you do not have to hard-code this information. As you want to generate a metadata-only assembly, you have to pass the -nowp parameter to SoapSuds to prevent it from generating a wrapped assembly. When using metadata-only output from SoapSuds, the client will have to (unlike the previous example) use the standard approach of registering channels and using Activator.GetObject() or new with RemotingConfiguration class for creating the remote objects. Note that the server implementation is not affected at all by the use of -nowp compared to the last project.